Creatine Monohydrate Explained – What is it and How Does it Work?

Creatine monohydrate is one of the most popular and highly researched supplements in the world of fitness.

Science has linked it to increased strength, power output and muscle mass and athletes from football players to weightlifters turn to creatine to enhance their physical prowess [1].

Despite its popularity, it’s been viewed in a bad light after it was rumored to cause side effects. However, there’s no evidence to support these claims and it’s since been proven to be safe to use [2].

On top of physical assistance, creatine also improves a range of cognitive functions, amongst other health benefits [3].

This article will examine creatine monohydrate from every angle to bring you information on everything, from how it works to safety.

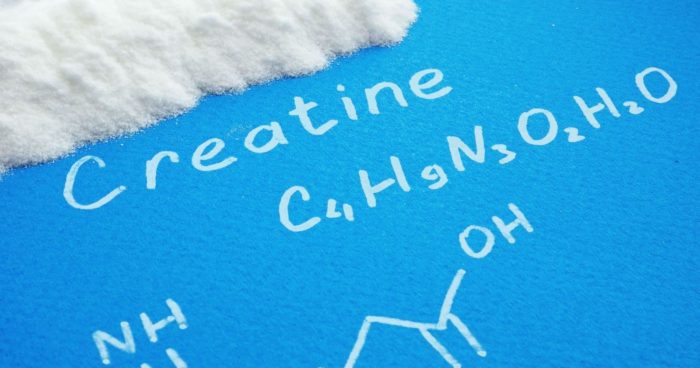

What is creatine monohydrate?

Although most commonly known in it’s supplement form of creatine monohydrate, this substance occurs naturally with our bodies and in a range of high-protein foods as creatine phosphate.

It helps your body reproduce the muscle energy compound, ATP, more quickly and efficiently, so you can work harder [1]. This is needed in weight lifting and other high-intensity sports where energy levels are depleted quickly.

This extra capacity during exercise can directly improve your ability to gain muscle, strength and enhance athletic performance [1].

Your creatine stores can fluctuate depending on a range of factors including how much meat you eat, your exercise levels and even hormone balance [4].

When you up your creatine intake, you can fill your muscle stores and create ATP more readily, which leads to a better physical performance during exercise [4].

Sources of creatine

Creatine is naturally produced in all vertebrates; therefore, we produce our own. It’s also present in a number of commonplace foods many of us eat regularly.

By eating more meat, we can supplement our diets with the compound and reap the performance-enhancing benefits it offers.

However, a number of factors means that it’s not always the most convenient option to consistently eat high amounts of these foods. For example, you may be vegan or vegetarian, or it may be too expensive to get all your creatine requirements from meat and diet alone.

That’s why many turn to creatine powder as a cheaper, more convenient alternative.

Here’s a list of the main sources of creatine:

- Red meat

- Poultry

- Pork

- Fish

- Dairy

- Eggs

- Creatine powder

[Related article: Best Pre-Workout Supplements for Women]

What does creatine do?

There are a number of ways this supplement can help to increase your athletic performance, along with cognitive function.

But what does creatine do in the body?

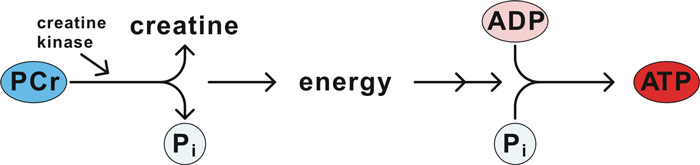

During explosive activity such as sprinting, HIIT sessions or weightlifting, your body goes into anaerobic mode.

When this happens, your muscles turn to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for energy. The compound breaks down by letting go of one of its three phosphate molecules to release energy. This leaves us with adenosine diphosphate (ADP).

Creatine is then utilized by the body to release a replacement phosphate molecule. This then attaches to ADP to return it to ATP, which is then ready to be used for energy once more.

It’s essentially to keep your creatine stores high so you can continue to create energy more quickly and efficiently.

Creatine benefits

Improved power output and athletic performance

Creatine has been shown to enhance the total power output of a workout or training session [5]. In a recent study, this ability to work more and increase total volume improved strength and fat-free muscle [6].

Strength athletes demonstrated a 15% increase in performance on bike sprints and a 6% improvement on bench press performance after supplementing with creatine for 28 days [7].

When supplementing with creatine, subjects in another study improved their endurance performance by 16% [8].

Enhanced brain cell signaling

The role creatine plays in creating energy is also put to good use in the brain. The cells within the brain use ATP energy to send signals and communicate with one another. Without it, they can’t perform these essential functions [9].

When supplementing with creatine, science has shown your brain energy levels are heightened, which can reduce fatigue [10].

The enhanced signal strength can also help to improve memory processes [11].

On top of this, the additional energy metabolism plays an important role in brain cell regeneration, which can help provide temporary relief from neurodegenerative diseases [12].

Increased hydration at a cellular level

Creatine monohydrate pulls water into the cells within your muscles. This increases the size of cells and may contribute towards heightened muscle growth [13].

Reduced myostatin levels

High levels of myostatin have been linked to slower new muscle growth. Creatine has been shown to reduce myostatin, therefore increasing the potential development of new tissue [14].

[Related article: Caffeine Anhydrous Explained: What is it and How Does it Work?]

How much creatine should I take?

One of the most talked-about elements of this supplement is how and when to take creatine.

Many advocate a loading phase to begin with, which has been shown to increase creatine levels in muscle by up to 40% [15].

This involves taking around 20g of creatine a day for 5-6 days to fill muscle stores, followed by a lower dose of between 3-10g to maintain optimal levels [15].

Other studies indicate that low-dose creatine, which sits at around 3g a day, can also help you fill your stores and achieve the desired benefits. However, this takes around 28 days to achieve [16].

Both a loading phase and low-dose supplementation can reap the rewards that come with optimal creatine levels, just at different rates.

While many opt for a loading phase to feel the benefits more quickly, low-dose may be a more cost-efficient option. These servings are easiest to add to your diet and maintain when supplementing with creatine powder.

[Related article: Best Pre-Workout Meals for Muscle Gain]

Creatine side effects and safety

This supplement has been under scrutiny as, for a while, it was thought to trigger potentially dangerous side effects. However, there’s no evidence to support that it’s unsafe or harmful to health [17].

Long-term studies have monitored the regular supplementation of creatine for up to four years and have not revealed any adverse symptoms [18].

As creatine monohydrate draws water to the muscles, many have linked it to dehydration and muscle cramps. However, science shows it can actually help to reduce the likelihood of these issues during exercise [19].

Final word

Creatine is one of the most highly researched supplements in the world. As such, you should feel comfortable in the knowledge that it’s proven time and time again to be one of the most effective and safest ways to boost your physical performance and mental function.

It can help to enhance power output, strength and encourages fat-free muscle growth.

Creatine also supports brain energy, enhances neurotransmitter communication and helps to protect cells against neurodegenerative diseases.

What’s more, it’s proven to be safe to use in the long term.

Creatine monohydrate is widely available and one of the best and purest forms of the supplement.

References

- Buford, Thomas W et al. “International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 4 6. 30 Aug. 2007, doi:10.1186/1550-2783-4-6

- Kreider RB, e. (2003). Long-term creatine supplementation does not significantly affect clinical markers of health in athletes. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- J, T. (1999). Creatine monohydrate increases strength in patients with neuromuscular disease. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- GA, P. (2001). Clinical pharmacology of the dietary supplement creatine monohydrate. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Aquiles Yáñez-Silva, Cosme F. Buzzachera, Ivan Da C. Piçarro, Renata S. B. Januario, Luis H. B. Ferreira, Steven R. McAnulty, Alan C. Utter and Tacito P. Souza-Junior. Effect of low dose, short-term creatine supplementation on muscle power output in elite youth soccer players. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition201714:5

- van Loon LJ, e. (2003). Effects of creatine loading and prolonged creatine supplementation on body composition, fuel selection, sprint and endurance performance in humans. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Earnest CP, e. (1995). The effect of creatine monohydrate ingestion on anaerobic power indices, muscular strength and body composition. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Graef, Jennifer L et al. “The effects of four weeks of creatine supplementation and high-intensity interval training on cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized controlled trial” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition vol. 6 18. 12 Nov. 2009, doi:10.1186/1550-2783-6-18

- Rae C., Digney A.L., McEwan S.R., Bates T.C. “Oral creatine monohydrate supplementation improves brain performance: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial.” Proceedings: Biological Sciences/The Royal Society. 2003 Oct 22;270(1529):2147-50

- Watanabe A., Kato N., Kato T. “Effects of creatine on mental fatigue and cerebral hemoglobin oxygenation.” Neuroscience Research. 2002 Apr;42(4):279-85.

- Yeo R.A., Hill D., Campbell R., Vigil J., Brooks W.M. “Developmental instability and working memory ability in children: a magnetic resonance spectroscopy investigation.” Developmental Neuropsychology. 2000;17(2):143-59.

- Esposito E., Cuzzocrea S. “New therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.” Current Medical Chemistry. 2010;17(25):2764-74.

- Dangott B, e. (2000). Dietary creatine monohydrate supplementation increases satellite cell mitotic activity during compensatory hypertrophy. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Saremi A, e. (2010). Effects of oral creatine and resistance training on serum myostatin and GASP-1. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Richard B. Kreider et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition201714:18

- Hultman E, e. (1996). Muscle creatine loading in men. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Peeters Brian M et al. Effect of Oral Creatine Monohydrate and Creatine Phosphate Supplementation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. February 1999.

- Schilling BK, e. (2001). Creatine supplementation and health variables: a retrospective study. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

- Greenwood M, e. (2003). Creatine supplementation during college football training does not increase the incidence of cramping or injury. – PubMed – NCBI. [online]

One Comment